The scary thing was how normal everything had come to seem, in a little more than five months. First-year students and their families moved into an all-but-deserted Harvard Yard, with traffic officers routing lone cars and enforcing the 20-minute unloading interval. Under a Science Center plaza tent, the newcomers met “Harvard College Welcome Team” members in personal protective equipment, and learned how to swab their nasal passages for coronavirus tests. Then it was off to pick up kits for their first meals, with snacks, to consume in their rooms during the mandatory initial isolation period.

For Convocation, on September 1, all assembled not in Tercentenary Theatre but at the “Harvard College YouTube Channel,” with available translation into Spanish and Chinese—and the obligatory warning: “If you’re living on campus, you can watch in your room/suite but should not gather in groups to watch.” That day, The Boston Globe reported that the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, which had geared up fast-turnaround coronavirus testing for dozens of colleges (a bottleneck nationwide that schools had to solve to reopen with any chance of controlling COVID-19 outbreaks), had completed its millionth test just days before.

At Convocation, President Lawrence S. Bacow and other speakers acknowledged the overlapping pandemic and racial-justice crises. Bacow urged students to “find your way to heal this world” (harvardmag.com/convocation-20). In an opening-day message the next morning, he wrote:

Now, we begin a semester unlike any other. What we do will be important, but how we do it will matter even more. When we get it right, we will celebrate. When we get it wrong, we will commiserate—and try again. The truth is that none of us knows what lies ahead, but we face this uncertainty together. I look forward to the day when we have all of this in our rearview mirror so I can see you again in person. Until that day comes, please take care of yourselves, your families, and each other.

In a revealing, even rueful moment, the opening words of his Morning Prayers text the same day hinted at what it cost to reopen the University on some basis for the fall term: “So, how did you spend your summer vacation?” Lamenting the pandemic-imposed loss of personal connection and ritual, Bacow invoked necessary new forms of ritual: “commitments to keeping members of our community safer than they would otherwise be”—among them, “Wearing a mask—enduring a testing regimen—these are daily celebrations of life—yours and the ones that you will save by being cautious and vigilant. Also a ritual.” (His greeting and Morning Prayers are covered in harvardmag.com/bacow-openingtexts-20.)

Reflecting rigorous preparation or efficacious new ritual (or both), the community got much right during the first month of the fraught semester.

Instructions and protocols were formidable. Arriving undergraduates had to self-isolate in their rooms until receiving a negative result on their first coronavirus test. (For subsequent tests, those 18 or older could swab unobserved; those younger had to return to the tent for supervised swabbing.) Thereafter, they could take 30-minute walks in the immediate vicinity—in groups of “up to two” students. After a third negative test, they could explore Greater Boston and gather in groups of no more than five. Effective September 9, socially distanced groups of up to 10 students were permitted when outside, with universal masking required except during dining (in groups of up to four).

Students living in the first-year dorms had to pick up their meals at Annenberg during their cohorts’ assigned times: 45-minute overlapping blocks from 7:30 a.m. to 10:15 a.m. for breakfast, and so on. First-years living in the Houses could get their meals only from their House dining hall. Then back to rooms, where the College provided microwave/refrigerator units, and HEPA-filter-equipped ventilating units put in place to trap virus-bearing aerosols. And so on.

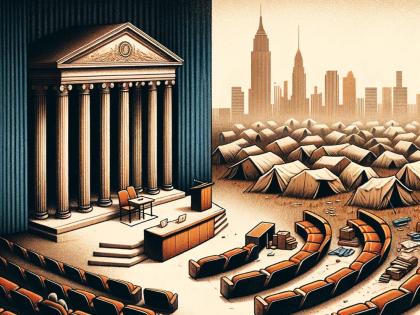

Moving in: The first-year arrival experience was tightly timed, socially distanced, and masked.

Photograph by Kristina DeMichele/Harvard Magazine

The payoff for the University’s tens of millions of dollars spent on testing, tracing, spacing, and modification was notable: from June 1 through September 27, a total of 73,847 tests administered had yielded 49 positive cases (nine undergraduates, 13 graduate students, and 27 faculty and staff members and affiliates; for current data, consult harvard.edu/coronavirus/harvard-university-wide-covid-19-testing-dashboard): a positivity rate within swabbing distance of zero. In fact, the systematic testing at Harvard and other local colleges, including of asymptomatic individuals, was so successful that it prompted concern in late September that the favorable campus results had masked a worrisome rise in the Boston area’s community positivity rate.

That favorable early experience attests both to the College’s decision to limit those in residence (when classes began, about 23 percent of usual enrollment: 1,491 undergraduates, including 1,150 first-years), and to superb compliance by community members. A reported riverside gathering of undergraduates beyond Mather House resulted in stern warnings about the community compact and the council set up to adjudicate violations, as well as a tough message from the dean of students, Katie O’Dair: (“[I]n the event that you attend gatherings along the river or near campus, drink in public, refuse to wear a mask, or do not maintain social distancing, you are not caring for this community, nor are you abiding by the agreement to uphold the local state and community guidance regarding COVID-19.”) The Crimson subsequently reported three first-year students in Mather were sent home after a party.

Most of the professional schools operated entirely remotely. The exception was Harvard Business School, which enrolled 731 first-year M.B.A. students (a typical class is 900) and 813 second-years. All first-year students were scheduled to be online until October, at which point they could learn in the hybrid classrooms. Second-year students began using the hybrid classrooms during the second week of September, with attendance in the school’s distinctive theater-style teaching spaces limited to 25 (about one-third or less of normal capacity). Those who study online are allowed to gather in groups of fewer than 10, or can log in from their dorms or homes. But elsewhere, it was a fairly quiet, anomic term. The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, which provides only minimal housing, reported 4,933 students enrolled full time, with most living in local apartments and studying remotely. (For the record, the College, which normally has about 6,600 students, reports 5,382 enrolled this year: many members of the class of 2024 deferred admission, and lots of upperclassmen and -women took leaves.)

Anecdotally, undergraduates in Cambridge reported they were bearing up: finding small groups of friends to meet for distanced meals, stocking their fridges (“We are allowed to go to Trader Joe’s,” on Memorial Drive, for munchie runs), and, among the upperclasses, navigating familiar surroundings (they were assigned to their regular Houses). They expressed awareness of their community obligations, to mask and so on: continual external, and internal, reminders to “keep you on your toes.”

And the fall version of remote instruction, they noted, differed significantly from the hurried pivot effected last spring. Scheduling was difficult, because sections were fitted to students’ disparate time zones, but if anything, one half-complained, the professors were trying so hard to encourage engagement and invite visits to office hours and create good assignments that the work really piled up. And where previously one could hang out in the back of a large lecture and scroll through messages on a phone, faces are ever-present and visible on Zoom: no place to hide. (For an in-depth report on instruction, see “School Goes Remote,” page 29).

Credit where credit is due. From late July through September 25, the college coronavirus case tracker maintained by The New York Times logged 123,000 cases—42,000 from early September alone. Those totals reflect, in part, the many large state schools that opened, under political pressure, without adequate resources for testing and tracing, in some cases ending up with new cases numbering in the thousands. Not a few, from the Universities of Wisconsin and North Carolina to private institutions like Notre Dame, had to shift quickly to temporary remote instruction in attempts to break the chain of transmission. Others, ranging from Princeton to Northwestern, had to pivot last-minute to all-remote instruction as the coronavirus spread and state and local regulations changed.

Harvard’s July decision to limit the number of resident students, impose all-remote learning, and draw on its resources to arrange a testing regimen with complete infrastructure (distribution and collection of kits, rapid reporting of results, and coverage extending to hundreds of undergraduates living off campus, announced in late September), has paid off, yielding a semester that has been unusual in the expected ways—so far. Given the challenges, a term that opened on the date scheduled, and has operated without a sudden interruption or dispersal of students from campus, has to be counted some sort of victory: a triumph, as Bacow said, of facing the uncertainties together. Whether the spring term can proceed as projected (with first-year students and others departing November 22, and seniors and others arriving in January) will depend on developments into December: the prevalence of the coronavirus and the flu, and how things unfold as the weather cools and hanging out turns inward.

There were unexpected pluses, as well. Late last spring, when the financial outlook seemed especially dire and the campus had emptied, senior administrators sent unambiguous signals that layoffs and furloughs were coming—possibly a lot of them. But as President Bacow enunciated Harvard’s principles for coping with the pandemic (protecting safety, mission, and people)—and as society at large tuned in to the economic damage being inflicted on front-line workers, and to America’s continuing racial inequities (and their brutal intersection in the pandemic)—the initial commitment to sustain service workers seemed to extend. There have been no formal announcements to that effect, but the College—operating its residences and dining facilities socially distanced, but at a fraction of capacity—has maintained its dining, security, and associated staffs intact. Much the same appears to be the case around the institution, even as performance venues and museums remain shuttered. Vacancies are not being filled, nor term positions extended, and incremental hiring has been curtailed—but these seem modest accommodations (along with nonunion pay freezes, pay cuts for senior leaders, and other economies) to keep the workforce essentially intact.

Nor is that all. Service workers have noted the University’s decision to offer campus parking at steeply discounted rates: a valued accommodation for those who cannot safely or confidently rely on public transportation operating on a curtailed schedule. More consequentially, Harvard created a new, paid time-off benefit, in force from September 20 to December 31, allowing up to 10 days “for care of members of the immediate family or household…who are well but whose schooling or care arrangements have been disrupted by COVID-19.” Given the remote or hybrid K-12 education prevalent throughout Greater Boston this fall, and unpredictable schedule changes, this news showed the University, which pays well and maintains broad employee benefits, navigating the pandemic as a responsive employer aware of sensible labor policies and practices followed by, say, the richer European countries.

Such accommodations have been made possible, in part, by earlier precautions. When financial markets collapsed in the spring, the administration warned deans to expect distributions from the endowment to decrease, rather than increase as budgeted. In August, feeling on firmer footing, that guidance was changed to level-funding for this academic year (see harvardmag.com/covid-fall-costs-20). And on September 29, when good endowment investment returns were announced (see page 20), the administration announced it would disburse an additional $20 million, from central funds, to the schools and affiliated institutions to help with pandemic expenses. As with the July decision to limit undergraduate enrollment to 40 percent of capacity or less, Harvard made financial plans that it has been able to keep, or improve upon.

Will this self-made run of luck hold? In a last-September interview with The Harvard Gazette, vice president and chief financial officer Thomas J. Hollister warned that University revenues would decline in both fiscal year 2020, ended last June, and the current year: a first since the Great Depression. “The key point,” he continued, “is the uncertainty. We face extraordinary, in some ways unprecedented, challenges related to the pandemic and ones that extend beyond it, including the economy, politics, societal inequities, and pressures in higher education.” He spoke in financial terms, but a sudden campus or community spike in coronavirus cases could still upend this semester, or shut down the next one.

Already, universities elsewhere have announced plans to remain entirely remote for the next semester, or to truncate the spring calendar (beginning later in winter—and flu season; eliminating spring recess). And the costs borne in adapting Harvard to the pandemic while sustaining the workforce amid depressed revenues will have to be made up elsewhere. The Graduate School of Education announced in September that it has “made the difficult decision not to accept doctoral applications for fall 2021 enrollment…in order to uphold our commitment to maintaining program quality and strong support for our current students.” Dozens of doctoral programs nationwide, including at Princeton, have made similar announcements or instituted sweeping restrictions, as at Columbia and Penn.

This suggests that even if Harvard keeps making the right bets—and its luck holds, as Massachusetts maintains effective control of the coronavirus—the world has changed, and will continue to do so in ways that would have been unthinkable last March.