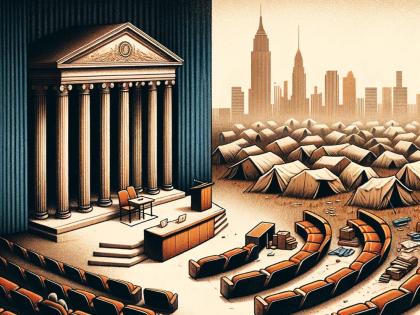

Harvard Law

I read with keen interest “The Education of a Harvard Lawyer” (January-February, page 38) by Nancy Boxley Tepper, my classmate. As I recall, she was one of five women in the class and I was one of three blacks. I noted with interest her comments about the phenomenon (“harassment”) of “Ladies Day” and the women’s invitation as 1L’s to Dean Griswold’s home for dinner and tea. She noted that her black male classmates were not singled out for “harassment” on our “day.” She is correct. I note however (ironically) that we three blacks were not invited to Griswold’s for dinner and tea. Was that a plus or a minus? I don’t know even yet!

I did have the pleasure years later of sitting center chair as Chief Judge of the D.C. Court of Appeals when then former Dean Griswold argued an appeal. It was a pleasure to be able to question him!

Ted Newman, J.D. ’58

Washington, D.C.

Nancy Tepper’s piece on her experience as an early Harvard Law School (HLS) woman and Lincoln Caplan’s counterpart review of economic drivers assessed in HLS (“Grinding Out Lawyers—by Grinding Down Students,” page 54) resurrected the cold sweats of my HLS experience and that of my 1960s cohorts. They also harked back to my semi-sociological “Fear and Loathing at Harvard Law School” (March-April 1995, page 44), which I revisited for the first time in years when this issue appeared.

“Fear and Loathing” detailed—based on interviews conducted in spring 1969 of several dozen classmates plus HLS professors and faculty psychiatrists—both the tacit pride of female students in being judged on their merits despite institutionalized harassment, and the price many students paid for HLS’s supercharged social-Darwinism. It concluded that HLS “did not treat merely the women badly. It treated everyone badly, and that treatment was no accident.”

Perhaps more telling were the rage-filled letters it elicited. These included one from a 1930s graduate noting “the Faculty’s dim bulbs, the dimmest…Frankfurter” and a supremely un-self-aware missive from an HLS professor disputing descriptions of faculty arrogance as “slandering a noble institution.” They also included confidential letters describing involuntary hospitalizations and flights from Cambridge as first-year final exams approached.

Michael H. Levin, J.D. ’69

Washington, D.C.

Reading Nancy Boxley Tepper’s Harvard Law School experience in the mid 1950s, I was struck at how accurate it would have been if it had described the academic experience of a female student 10 years later. There were only three differences: 25 women in the 500+ entering class in 1963 compared to 12 in 1955; the absence of a private dinner of all 25 female students with Dean Griswold and his wife at their Cambridge house; and—happily—the discontinuation of “Ladies’ Day,” when professors directed all their questions to the female students in class. Tepper had no complaints of discrimination against the female students in class or in the hiring process. Indeed, there was virtually nothing in her memoir that would raise feminist hackles or cause anyone to think ill of the law school.

What would have made a more probing piece would have been an exploration of Harvard Law’s extremely narrow definition of meritocracy, the grant of the faculty’s adulation and attention solely to the top ranking students in the class (which number included Tepper). The apex of prestige was, and remains to this day, ranking among the top 25 in the first year’s exams. This ensures an invitation to join the Harvard Law Review and to enjoy the cascade of privileges described in detail by Tepper, the most unexpected being a personal key to the Harvard Law School library. To be frank, if a student did not rank in the top 5 percent academically, it took a heroic effort not to be ignored by the faculty for the last two years of law school. For many, it became an unfriendly and lonely experience. (I place myself among the relatively content minority, and I enjoy the 10-year reunions.)

There are a multitude of personal qualities that make a lawyer effective. The law school’s exams test the ability to reason quickly and synthesize legal arguments in a well-written manner. They essentially ignore other legal skills such as reasoning well but more slowly, the ability to remember facts and arguments and articulate them orally, good judgment as to people and their behavior, etc. Thus, the school’s accolades often miss its most outstanding graduates. For example, the two best known members of my class of 1966, retired U. S. Supreme Court Justice David Souter ’61, J.D. ’66, LL.D. ’10, and professor of constitutional law Laurence (Larry) Tribe [Loeb University Professor emeritus], were not invited to join the Law Review.

John Impert, LL.B. ’66

Seattle

In the article, Tepper presents her experience as a Harvard Law School student, including earning the rare position of a woman on the Law Review, and her subsequent legal career. It includes the tale of how she got her first legal job out of law school at an elite New York City law firm.

Neither Sandra Day O’Connor, first woman Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, nor Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Ms. Tepper’s fellow editor of the Harvard Law Review, who was first in her class when graduating from Columbia Law School, could get a job as a lawyer with any law firm, let alone a “white-shoe law firm” in downtown Manhattan.

Given the foregoing, I thought Ms. Tepper might have commented a bit more about the uniqueness of her gaining her first job out of law school than merely stating, “So much for the rumor that these firms would not hire a woman lawyer.”

Jerome W. Breslow, LL.B. ’59

Potomac, Md.

Is there a conflict between Tepper’s article and Caplan’s book review? The former gives credit to Dean Griswold for fighting to admit and welcome women to HLS, whereas the latter calls him “infamous” for his “grilling” of Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

William G. Dakin ’57, LL.B. ’60

Washington, D.C.

Editor’s note: Tepper’s tone, word choice, and context led the editorial staff to conclude that any conflict is minimal. Griswold did indeed admit women, but in many accounts, only grudgingly. Tepper is generous, and appears made of stern stuff. Other accounts have him asking the women how they could justify taking the place of male applicants whom they displaced. In any event, the environment Tepper describes changed for everyone starting in the 1980s and 1990s, as Caplan notes.

Thank you for a fascinating article by Nancy Boxley Tepper.

I have known since my days at Harvard, in the 1950s, that being a member of the Harvard Law Review was a high honor predictive of a great career in the legal profession. However, I had no idea how anyone was selected for the Review, or what the work involved.

Tepper’s absorbing account of her experience, as well as her report of a return visit to a Law School classroom, was an article I chose to copy and send to friends.

The Reverend Fred Fenton ’58

Seal Beach, Calif.

While Dean Griswold takes his lumps in your last issue (“infamous for his grilling” of Justice Ginsburg, “forbidding, uncompromising”), let it be noted that when I, as a disaffected second-year student, sought his approval for studying Russian in the Yard in place of yet another course, he immediately understood my state of mind and readily agreed, helping me manage three subsequent assignments at our embassy in Moscow.

Robert F. Ober Jr., J.D. ’61

Foreign Service (ret.)

Litchfield, Conn.

Loneliness

Your recent article on loneliness (“The Loneliness Pandemic,” January-February, page 31) caught my attention. You speak of loneliness in every generation except what the seniors are suffering. I am 83 and a half years old and count every day active seniors like myself who have had to quarantine, away from the few friends who are still alive (I lost three good friends this year), and have had to cope with being home and with depression. Let your researchers talk to people of all ages.

Esther M. Gold

Springvale, Me.

I was greatly saddened to read the story about loneliness in the current issue. What was missing, of course, is anyone asking the question of why a Harvard student would be spending 20 hours a week doing volunteer work such that it left him with the personal emptiness the article describes. Unfortunately, I suspect that the reason might be that it was a pattern he had developed in high school or prep school as he was trying to get Ivy League admissions committees to think that he was a worthy person, and therefore a worthy candidate for admission. Maybe these patterns would be worthy of college presidents’ Freshman Addresses in future years.

Perry Karfunkel, G ’78, M.D. ’80

Plymouth, Mass.

Acupuncture

There have been a number of studies, documented in the website UpToDate that show no more than a placebo effect from acupuncture as practiced today (see “How Acupuncture Relieves Inflammation,” January-February, page 11). Some practitioners have come to the conclusion that, if the patient feels it helpful, why not go with it. As the great Dr. Peabody said, “To care for the patient is to care for the patient.”

Electroacupuncture will need clinical trials to prove its worth.

Tristram Dammin ’70, M.D.

Instructor, Boston University School of

Medicine (Emergency Medicine)

Professor Qiufu Ma replies: I agree that clinical studies are needed to examine whether electroacupuncture can reduce systemic inflammation in humans. I might consider it unlikely that placebo effects can powerfully suppress severe, acute cytokine storms, as we found in our study with mice. However, for chronic inflammation and pain treatment, more studies are needed to determine how acupuncture effects partially overlap with placebo effects. We are still struggling to design an appropriate acupuncture control needed to conduct this research in humans.

The article reports “acupuncture uses fine needles to stimulate points on the body’s surface that scientists believe send nerve and biochemical signals to corresponding organs and systems.” To study this they run electric current between two needles inserted in hind limbs or abdomen of mice. As with many acupuncture studies, there is a tantalizing suggestion of benefit. Although by their very own definition they didn’t actually study acupuncture.

A few questions. How standardized are acupuncture sites among practitioners around the world, or in China, over the 3,000 years of their use? Hind limb and abdomen are large parts of mouse and human anatomy. How standard is the technique? More simply, is acupuncture well enough defined to be considered “a thing?” What about human data? And statistical significance?

What is the biological plausibility that being stuck with pins in just the right places will prevent death from septic shock? Host defenses against microbial attack are exquisitely evolved throughout the animal kingdom—powerful, intricate, highly regulated, knife’s-edge precise, and necessary for life. Do the authors believe that pricking a hind limb can quickly correct “errors” made by these primordial systems? Finally, if they do in fact modulate the immune system, wouldn’t it seem likely that they will have adverse effects, as do essentially all other immunomodulatory interventions?

Thomas E. Finucane ’71

Brookline, Mass.

Enormities

Re: Lincoln Caplan’s defense of his use of the word “enormity” (“An Amplification and Errata,” January-February, page 66) when he meant “magnitude” in his profile of Noah Feldman, against reader criticism: I was glad to see Caplan citing a 1959 Webster’s second edition rather than some more newfangled and permissive dictionary such as Webster’s third. My own Webster’s second, a 1970 printing, lists the “immensity” meaning as “rare,” after two other meanings relating to “monstrous” or “wicked.” Caplan says “the term’s meaning is in transition from one conventional understanding (‘enormity’ as ‘immensity’) that some still read it to mean, to a different understanding (‘the extreme of something morally wrong’).” It could be the transition is going in the other direction.

Ira Stoll ’94

Boston

Evocative Shoes

I was moved by the image accompanying Che R. Applewhaite’s “A Common Underground” (The Undergraduate, January-February, page 27) of Vincent van Gogh’s painting Three Pairs of Shoes, on display in the Harvard Art Museums. Each pair of worker’s shoes has a personality that depicts the notion that workers shouldn’t be seen as a “homogeneous mass.”

Reva Luxenberg

Delray Beach, Fla.

Climate Change

I was disappointed that in the climate crisis feature (“Controlling the Global Thermostat,” November-December 2020, page 42), there was not a single mention of the contribution of animal agriculture to climate change and global GHG emissions. Focusing solely on the decarbonization of the energy system misses the fact that to avoid major catastrophe, radical changes are also needed in the global food system.

The piece focused entirely on wide scale technological and political actions, but neglected the single most important individual mitigation action that we can all take to address the climate crisis: switch to a predominantly plant-based diet.

Daniella Allam ’09

Richmond, Calif.

Editor’s note: Please see the March-April 2020 cover feature, “Healthy Plate, Healthy Planet,” which covered exactly these issues in detail, as did earlier Right Now reports “Eating for the Environment” (March-April 2017, page 11) and “Climate Change and Crops” (November-December 2017, page 14).

It’s wonderful to hear about the research underway at Harvard to address the climate crisis. For me, though, there is a missing element in this story. Financial investments are driving global climate impacts. That’s why many universities, including Harvard’s peers, have chosen to divest their endowments from the fossil fuel industry. Harvard has lagged on this issue, and on other aspects of socially responsible investing (for example, it’s still invested in another infamous industry, private prisons). I urge the administration to pay attention to calls from students, faculty, and alumni for divestment. Organizations like Fossil Fuel Divest Harvard and Harvard Prison Divestment Campaign are setting an agenda the University should follow.

Maya Fischhoff ’93

Ada, Ohio

The article exemplifies the far-reaching thinking needed to cope with the climate crisis. Unfortunately, it offers scant hope for a long-term solution.

Dwight Eisenhower once said you can’t solve a problem by making it smaller. We need to expand our thinking to include both overpopulation, a major contributing factor, and expanding civilization into space, a potential contributor to a solution.

How can the world sustain its current population of 7.7 billion, estimated to grow to 11 billion by 2050? Gerard O’Neill, a visionary scientist and professor, saw habitats in space as a contributing solution. His 1970s book The High Frontier: Human Colonies in Space proposed huge orbiting cylinders where rotation would create “gravity” similar to Earth’s and internal environments could be maintained however necessary. These wholesome and attractive habitats would be manufactured in space from materials lifted from the moon.

O’Neill passed away in 1992, but technological progress has enhanced the feasibility of his ideas. Reusable launch vehicles reduce cost and increase payloads. Nanotechnologies promise materials strong enough for cables from Earth’s surface to geosynchronous orbit for a “space elevator.” Artificial intelligence and remote operations demonstrated by exploration of Mars and asteroids hint that mining materials from the moon or asteroids, construction, and manufacturing in space could be feasible.

Can the required technologies be matured and scaled up quickly enough? Neil Armstrong made his “giant leap for mankind” 2,978 days after President Kennedy set a moon landing as a national goal. The technical ability to solve a problem is seldom the greatest barrier to solution. The real challenge is building a sufficiently powerful constituency to compel a solution. The climate crisis provides an opportunity to do this.

Existential crises often force fundamental changes in history’s course. We are now at such an inflection point. To restore our planet, we need to expand into space to reduce the burden on our beautiful world. Can we do this? O’Neill quotes Robert Goddard, the father of American rocketry: “It is difficult to say what is impossible for the dream of yesterday is the hope of today and the reality of tomorrow.”

Richard Dunn, M.P.A. ’80

Fredericksburg, Va.

Thank you, Professor Schrag! Thank you for having the courage to bring up what should not be climate change’s “dirty little secret”—but instead is the penultimate question before any major policy decisions are made. I am in your debt because you literally helped to heal a totally unnecessary rift in my relationship with my three daughters (15, 17, 19—and I’m proud to say as a conservative dad that they are passionate and active liberals) .

For the last couple years I have tried to share with my daughters my concern about the “point of no return” and whether that means there will be little or no return on investments in decarbonization. My daughters have grown very frustrated with me—for what they have called my hatred for science, only somewhat jokingly.

As I have struggled to have a serious discussion with them about how “the science” itself points to extreme caution especially about unilateral decarbonization, I was a bit shocked when you so eloquently stated this issue. My daughters were able to see that I don’t hate science, but that I am following my own “prescription for common sense.”

My time at Harvard taught me how important it is to not be content with learning what to think, but instead to learn how to think. I have tried to pass this value to my daughters in a formula—B>1?Deep. This formula or prescription simply means to “Be more than One Question Deep,” and it is applied by recognizing logical fallacies, unsubstantiated statements of fact, and more generally understanding the concept of statements that “beg for an obvious next question.” Further, it requires a commitment to disabuse yourself of ad hominem retorts like “You hate science.”

This wonderful article by Harvard Magazine has provided for great discussions in my family. For instance, Bill McKibben states that “Solar and wind power are now the cheapest way to generate power around the world.” It took my daughters quite a while to see what the next obvious question is—but I was proud when they were able to formulate this important “next level” thought exercise:

If solar/wind power is the cheapest way to generate power, then the obvious question is “Why do we need carbon taxes and regulations to force people/countries to switch to this carbon neutral energy?”

It was wonderful to actually get to discuss such an important issue with my daughters in a way that actually brought us to a closer understanding rather than division. And Schrag also gave us a concept that we could all agree on—“Leadership on this issue means not just charging ahead,” he emphasizes. “Leadership means getting other people to follow. The goal must be to decarbonize the U.S. in a way that looks as attractive as possible” to the rest of the world.

I urge Schrag to continue to ask the logical next questions, especially when any fact or truth gains the status of “dirty little secret.”

Eldon Eric Johnson ’91

Sarasota

Editor’s note: Carbon taxes are designed to capture the true cost of using carbon-based fuels, much of which is in the form of externalities (like global warming or particulate pollution) not reflected in market pricing. So the case for carbon taxes does not depend on the current cost of competing sources of energy which do not produce similar externalities. Most economists feel that carbon taxes are more efficient than regulations, but regulations are often the politically palatable solution, not the one that would be adopted purely on efficiency grounds. You may find “Time to Tax Carbon,” September-October 2014, helpful.

Noticeably absent in the article was more than a passing reference to the role of fossil-fuel divestment: “[Bill McKibben] advocates divestment of fossil fuel investments (including at Harvard)....” Really? That’s all you can say? The article demonstrates Harvard’s leadership in research: Isn’t it time for Harvard also to show its leadership in divestment from fossil fuels? To quote Dan Schrag: “Leadership means not just charging ahead, leadership means getting other people to follow.” I’m neither an economist nor a scientist, but even casual reading of the news strongly indicates that the winds are blowing toward renewable energy, which other institutions from the UC system to Oxford have recognized.

Having missed the opportunity in this article, perhaps the magazine can show its leadership by reporting about the economics of climate change, including the divestment movement to which thousands of students, faculty, and alumni have given their support.

Adelia Moore ’71

Canaan, N.Y.

Editor’s note: For some relatively recent status reports, please see “An Overseers Challenge Slate, and More on Fossil-Fuel Divestment” and “Addressing Climate Change,” among other articles.

“Adaptation and Amelioration” could only be temporary balm to mankind’s thoughtlessly profligate and wasteful consumption. Personal habits matter. Instead of relying on rich governments’ environmental governance and policy to forcibly wean us from our dependency on climate-changing fossil fuels, each of us could reduce our household energy and resource use, recycle more and consume less. If all of us individually took care to minimize our harm of the natural world by downsizing his carbon footprint, we could collectively and substantially mitigate the ecological assaults burgeoning humanity continues to inflict. The problem is that those of us who reduce, reuse, recycle, and deeply think about our adverse lifestyles remain in the minority. Most continue on our nonchalant route to ecological ruin because there is not a large enough disincentive to avoid gas-guzzling SUVs, the long commute from energy-sapping four-bedroom suburban homes, and to rid our addiction to disposable consumer goods carried in plastic shopping bags. It is high time each of us took personal responsibility for lessening the impact of the lives we lead. If we drove less, walked and cycled more, used small fuel-efficient cars and public transport, the world would breathe a sigh of relief. Such daily concerted effort by the billions each day could add up to tip the balance back in favor of Planet Earth. It is also unfair that those who care enough to act locally will be made to suffer the same harmful consequences of global warming and ecodegradation as the thoughtless and careless.

Regulations need to be enacted and enforced, and we need to vote in governments that genuinely care about Earth’s medium- to long-term outlook. We can continue to pretend that global warming and irretrievable ecodegradation will not prevail because we possess the ingenuity to fix our assaults on Mother Nature, but in the end, the laws of physics will prevail. When the environment is turned into an economic transaction and political weapon, it does us all well to recall the caution:

When the last tree is cut down,

The last fish eaten,

And the last stream poisoned,

You will realise that you cannot eat money.

Joseph Ting, MBBS MSc (Lond) SCCL (Melb), BMedSc PGDipEpi DipLSTHM FACEM.

Adjunct professor, School of Public Health and Social Work

Kelvin Grove, Brisbane, Australia

Edwin Binney’s Philanthropy

I was gratified to see the late Edwin Binney 3rd recognized for his generosity in donating his very large and important collection of dance material to Harvard’s Theatre Collection (Vita, January-February, page 36). The article, however, failed to mention that the Edwin Binney 3rd collection of Ottoman Turkish art, one of the largest and richest ever in private hands, comprising numerous miniature paintings as well as other media, was divided equally between the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Harvard Art Museums, after having been exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Portland (Ore.) Museum of Art, and the San Diego Art Museum. And recently, over three decades after Ed’s death, his important collection of European prints on Orientalist themes found a permanent place in the Harvard Fine Arts Library, thanks in large part to the efforts of András Riedlmayer.

Walter B. Denny, Ph.D. ’71

Distinguished Professor of the History of Art & Architecture

University of Massachusetts, Amherst

Editor’s note: The strict Vita format forces authors to omit many otherwise desirable details from their texts. We welcome this additional information.

I read with interest the recent article by Madison U. Sowell and was compelled to share yet another instance of Binney’s generous contributions to Harvard. Not only a contributor to the Harvard Theatre Collection, Binney was also one of the most important donors of Islamic art for the Harvard Art Museums, both for the quality and breadth of his gifts. Most of the Islamic works in Binney’s collection were divided between the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Harvard Art Museums. The Harvard Art Museums now hold about 175 works from Binney’s collection. These range from the tenth to the nineteenth century, and while most are from the Ottoman Empire, he also collected fascinating works of art from the greater Iranian region and North Africa. The strength of his collection was in works on paper, including paintings, calligraphy albums, Qur’ans, and illustrated manuscripts of poetry. He also acquired important examples of ceramics, textiles, metalwork, and carved stone. The Fine Arts Library also holds a collection of European prints that belonged to Binney.

Two of our most iconic Binney objects are:

Fragment of a velvet yastik (cushion cover), Turkey, probably Bursa, Ottoman period, 2nd quarter of 16th century. Cut, voided silk velvet with brocaded silver thread. Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum, The Edwin Binney, 3rd Collection of Turkish Art at the Harvard Art Museums, 1985.295.

Woman gazing at her reflection, illustrated folio from a manuscript of the Rawda al-Ushshaq (Garden of Lovers) by Arifi, Turkey, Ottoman period, c. 1560. Ink, opaque watercolor and gold on paper. Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum, The Edwin Binney, 3rd Collection of Turkish Art at the Harvard Art Museums, 1985.216.23.

Mary McWilliams

Calderwood Curator of Islamic and Later Indian Art

Harvard Art Museums

Political Diversity

I was struck by “Broadening the Faculty’s Ranks” (January-February, page 18), which made me wonder as we slice and dice the population and try to be sure everyone is represented, why do we not include people of diverse political leanings, e.g., conservatives, and measure how we are doing. These have largely been eliminated, even canceled, from the academy, if not from the entire education industry.

I’d argue diversity here—and the intellectual thought both sides bring, and the student debate that ensues—is more important to our country in the education of our youth than is a faculty member’s skin color or sex or sexual orientation, although fairness in employment to diverse candidates in this regard is important as well.

Bob Flaherty, M.B.A. ’71

Brookline, Mass.

Renaming

Isn’t there an obvious solution (“Names, Reconsidered,” January-February, page 26)? Keep the name but change the person it stands for. My first choice would be Amy Lowell. There’s no reason to rename it Amy Lowell House. I lived in Lowell House for three years and never heard anyone call it Abbott Lawrence Lowell House. That’s because no one ever did. Simply start saying Lowell House is named in honor of a great poet. Stop discussing A.L.L.’s inadequacies. The poetry community would be thrilled. Ten thousand feathers would remain unruffled.

Dudley H. Ladd ’66

Milton, Mass.

Editor’s note: The discussion prompted by Lowell House’s faculty deans explicitly mentions Amy Lowell, among other options. See harvardmag.com/lowell-name-debate-20.

The Overseers

As Dean Khurana tirelessly reminds us, Harvard College sets itself the mission of educating the citizens and citizen-leaders of our society. With its nakedly antidemocratic decision to limit the number of alumni-nominated Overseers to a token one-fifth of the Board (“Overseers Overhaul,” November-December 2020, page 23), the University’s leadership admits that it has failed in this task: when Harvard’s administration is on the ballot, its graduates cannot be trusted to exercise real political power. One has to ask what this implies about the quality of the current leadership’s own governance.

Zeke Benshirim ’19

Boston

Advisor Removed

Sometimes I cringe at the liberal bias of Harvard, but the removal (canceling) of U.S. Representative Elise Stefanki (R-N.Y.) from the senior advisory committee of the Harvard Kennedy School’s Institute of Politics is the first time that I have actually felt ashamed to be a graduate of Harvard. What on Earth ever happened to the concept of free speech?

Even if I am sure that the other person is wrong or a liar, in my United States that person has a right to express their opinion in words (or by voting). Apparently Dean Elmendorf disagrees. He also fails to recognize that the title “U.S. Representative” means that Stefanik was freely elected by a significant number of American citizens. Those same citizens have every right to remove her from Congress in the next election, but Elmendorf’s action to remove Stefanik confirms the feelings of millions of Americans that it is dangerous to say anything that disagrees with the current liberal power bloc in this country. Elmendorf and his colleagues should be deeply ashamed of his actions.

Donald D. Runnells, Ph.D. ’64

Fort Collins, Colo.

Editor’s note: See harvardmag.com/stefanik-iop-21, and for President Lawrence S. Bacow’s perspective on speech on campus—and the standards the institution applies to those appointed to lectureships or fellowships, or serving on advisory committees, and other matters—see harvardmag.com/bacow-on-polarization-21.

TO A FAIR-MINDED PERSON, the removal of N.Y. Representative Stefanik must have been made by people that neglected to listen to her short five-minute appeal for peaceful and respectful debate. (Please see attached video from C-SPAN: Stefanik House Floor Remarks on Objecting to Certain Electors - YouTube. Rep. Stefanik twice condemned the violence of the riot and praised the protection of police and staff for which she got a standing ovation from both sides of the aisle. She then went on to state that the House of Representatives is the “place where we respectfully and peacefully give voice to the people we represent across our diverse country.”

Her point of debate was not fraud but that in a handful of states the rules for the 2020 election were changed in a manner not prescribed by that state’s constitution. She didn’t accuse anyone of fraud yet this is why she has been removed from the IOP Advisory Committee. How we make the rules for conducting an election IS a policy debate and worth having. Yet, Dean Elmendorf stated: “These assertions and statements do not reflect policy disagreements.” Somebody is out of line here and acting a bit hasty. It’s not Rep. Stefanik.

Rep. Stefanik also pointed out that Democrats objected to electors after GOP wins in 1989, 2001, 2004, and 2017. And, that House debate was the place and time to do it, which is precisely why the Speaker of the House gave her five minutes of time to make her point. Apparently, that was too much time for Harvard?

Thankfully, this is an easy fix. Let the temperature come down, watch the video, “take in” her sincere and well-reasoned points and restore her to the committee immediately.

Harold Goetsch, M.B.A. ’97

Sudbury, Mass.

Sports Semi-fan

Although I’m not really much of a fan of sports, your article “The Sports Critic” (November-December 2020, page 64) was surprisingly evocative. The work of a sportswriter focusing on individuals and the greater themes of the game, rather than breaking news, reminded me very much of the charming multimedia experience 17776, by Jon Bois. I must admit, it roped me in in part because, at first, I didn’t even know that it was about football! I’d recommend that anyone whose interest was piqued by The Sports Critic consider giving 17776 a read, a watch, and a listen.

Amitabho Chattopadhyay, A.L.B. ’19

Berkeley

Mountain Biking

Re: “Defy the Doldrums” (January-February 2021, page 12F).

What were you thinking??? Mountain biking and trail-building destroy wildlife habitat! Mountain biking is environmentally, socially, and medically destructive! There is no good reason to allow bicycles on any unpaved trail!

Bicycles should not be allowed in any natural area. They are inanimate objects and have no rights. There is also no right to mountain bike. That was settled in federal court in 1996: https://mjvande.info/mtb10.htm. It’s dishonest of mountain bikers to say that they don’t have access to trails closed to bikes. They have EXACTLY the same access as everyone else—ON FOOT! Why isn’t that good enough for mountain bikers? They are all capable of walking....

Mountain bikers also love to build new trails—legally or illegally. Of course, trail-building destroys wildlife habitat—not just in the trail bed, but in a wide swath to both sides of the trail! E.g., grizzlies can hear a human from one mile away, and smell us from five miles away. Thus, a 10-mile trail represents 100 square miles of destroyed or degraded habitat, that animals are inhibited from using.

Mountain biking, trail building, and trail maintenance all increase the number of people in the park, thereby preventing the animals’ full use of their habitat. See https://mjvande.info/scb9.htm for details.

Mountain biking accelerates erosion, creates V-shaped ruts, kills small animals and plants on and next to the trail, drives wildlife and other trail users out of the area, and, worst of all, teaches kids that the rough treatment of nature is okay (it’s NOT!). What’s good about THAT?

In addition to all of this, it is extremely dangerous.

Mike Vandeman, Ph.D.

San Ramon, Calif.

Errata

The listing for Studying with Miss Bishop in the January-February issue's Off the Shelf column (page 52) misspelled the name of the book’s author, poet and critic Dana Gioia, A.M. ’75. And in that issue’s College Pump (page 60), a tribute to the late Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin was marred by the misspelling of her name. We regret both those errors.