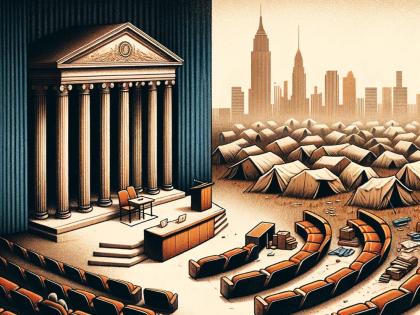

In 1946, shortly after the end of World War II, the philosopher Hannah Arendt wrote to her colleague Karl Jaspers in Germany about her five previous years in the United States. “There really is such a thing as freedom here and a strong feeling among many people that one cannot live without freedom,” she noted with faint surprise. Perceptively, though, she added, “The fundamental contradiction in this country is the coexistence of political freedom and social oppression.”

During the next two decades, artists, intellectuals, and politicians in the NATO countries generally believed that the concept of freedom was valuable, making it a cornerstone of their self-definition, especially in drawing contrasts to totalitarian states (fascist, Communist, or otherwise). But this superficial consensus masked widespread disagreement about just what freedom meant, and whether the “Free World,” particularly including postwar America, had come even remotely close to attaining it.

Louis Menand’s ambitious new 735-page history The Free World: Art and Thought of the Cold War (to be published in late April by Farrar, Straus, and Giroux) chronicles the debates and apparent contradictions that shaped the American cultural world between the fall of the Nazis and the thick of America’s war in Vietnam. Those two decades saw abstract expressionism, but also McCarthyism; Jim Crow and the civil-rights movement; and worldwide decolonization, even as superpowers fought wars by proxy that would determine the fate of smaller countries. Through wide-ranging chapters, Menand traces how the convergence on freedom as “the slogan of the times” imparted unusual urgency to art and culture amid the era’s political debates over topics such as experimental music, international black thought, existentialism, and second-wave feminism. Everything from John Cage’s 4'33"to comic books could be debated as either resistance to, or a slide toward, the loss of freedom. The resulting book, he writes in his preface, is “a little like a novel with a hundred characters,” ranging from James Baldwin to Brigitte Bardot, from George Orwell to Andy Warhol.

Menand reconciles the perspectives of these individual artists and thinkers with large-scale transformations, such as demographic or technological change. Thus, he says, the question of “What are the major social forces that push in a direction that makes it possible to paint the American flag, or a soup can?” pairs with “What are the things going on in the street that lead to a major change in art? And what did Jackson Pollock think he was doing when he painted? What did Allen Ginsberg think a poem was supposed to be?”

By moving back and forth between these perspectives, Menand aims to explain how unrelated phenomena coalesced into movements, trends, and mentalities. “Pollock and jazz and spontaneous composition of poetry all look similar,” he says, “even though they happen for completely disparate reasons.” For instance, one chapter begins with the ideas informing French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss’s new thinking about the origin of cultural difference and ends with photographer Edward Steichen’s exhibition “The Family of Man,” a controversial attempt to depict common humanity around the globe.

He also argues that the “cultural Cold War,” a now-common label for the U.S. government’s promotion of artists like Pollock and Louis Armstrong as advertisements for capitalist democracy, was actually less overt than some historians have contended. “When you get into what the artists were doing and what the people were writing and thinking about…it wasn’t really ideological,” he says. “I got away from the idea that the explanation for everything has something to do with the deep state. That was a feature of Cold War culture, but it was not what influenced most writers and painters and thinkers.” When people started to realize, relatively late in the period, that organs like the Congress for Cultural Freedom and the National Student Association were covert fronts for the CIA, it turned out as well that even those receiving funding (like Partisan Review) hadn’t received much direction. The CIA funded them specifically because they criticized the government, because of “the propaganda value of dissent.”

Work by the Bass professor of English will be familiar to many from decades of essays and reviews on Cold War-related topics for The New Yorker, where he is a longtime staff writer. Although Menand stresses that he “didn’t want to write a survey that covers everything, the cross currents that characterize The Free World share affinities with the sweeping scope of Menand’s earlier books The Metaphysical Club (for which he won the Pulitzer Prize for History in 2002) and American Studies. Recent alumni may also have taken one of his popular courses on the cultural history of the Cold War. But this latest work consists of new material—the culmination of years of thinking, stretching nearly as long as the period the book covers.

Menand also contributes to work across a number of fields simply by helping debunk a number of confabulations, often well-known, that close examination proves couldn’t possibly be true. Pollock’s Mural was not sliced into its final form by Marcel Duchamp. And Cage and Warhol both liked lying to interviewers about their lives for the fun of it. “They didn’t think of it as lying, for some reason,” Menand says. “They just thought, I’m playing a game here, and this is how the game is going to work.”

Menand found himself changing his mind substantially about almost all the figures in his book as he wrote it. “I had certain received ideas about Jack Kerouac, John Cage, or Susan Sontag based on relatively little knowledge of what they actually did. But once you start digging into it, usually your view of what they were all about changes quite a bit….Part of the reason you write is to find out what you don’t know,” he explains. “That’s what you want to convey to the reader—you think you know what Elvis Presley was up to, but maybe you don’t.”