Paul Reville, former Massachusetts secretary of education, now directs the Harvard Graduate School of Education’s Education Redesign Lab, a research center that aims to remake public education to meet today’s inequality crisis. He recently spoke with Harvard Magazine about reopening schools this fall, online learning, and the opportunities to transform U.S. education stemming from the challenges posed by COVID-19—including the idea of providing every student an individualized “success plan,” and convening “children’s cabinets” to address all of children’s needs in a community beyond just K-12. The following Q&A has been edited for clarity and concision.

Harvard Magazine: We have heard a lot about reopening schools in recent weeks. How do you think cities and states should weigh the public-health risks of opening schools against the risks of continuing to keep children out of school? What's the right way to think about that problem?

Paul Reville: Well, it's a very tough balancing act that local jurisdictions all across the country, all across the world, really, are struggling with, in terms of the particular health conditions that prevail and their geographic area, and then the demographics of the population that they're working in. For example, bringing college kids back to campuses is a different thing than bringing preschoolers back to a preschool.

So what we're going to see is a highly variable set of responses distributed across a continuum, from some places who aren't going to bring anybody back because it's just too risky now…to other places—Orange County, California, I think recently said that we're going to go ahead and bring everybody back. And we're not worried about masks or anything, we're just going to go ahead and do it.

And then the overwhelming distribution in the middle, where we're going to see a lot of hybrid models, many of which honestly haven't been very well thought out in terms of what that actually means and how that's going to happen. Because one of the problems in our field is we've been rather backward with respect to the use of technology in education. We've been a resistant industry by comparison with business or medicine, for example. And so we weren't really ready for this transition, and it happened virtually overnight. We had an emergency response over the last three months of the last school year. Honestly, I haven't seen the time and energy dedicated in the summer that would lead you to believe that most school systems are ready to perform at a state-of-the-art, high level with respect to doing online education.

There are many good reasons for that, not least of which are cost factors and union contracts that can control the amount of professional development and training you can do. There are just decisions that many districts have not made about what platforms they're going to use, what applications, what curriculum. They haven't allowed for time for teachers to adapt.

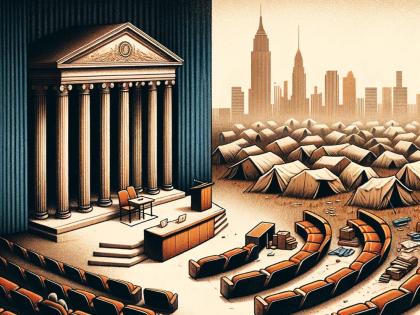

Of course, there are exceptions to this rule. There are some districts and schools that are doing fine, because they've had experience with this, they have embraced technology. So it’s very hard to generalize, but I most worry about our cities and our rural areas, where they don't have a lot of resources, the cities where they have great issues of scope and scale and in complexity, and where the failure to meet the needs of students is going to have huge consequences in terms of equity. The disadvantaged are going to fall further behind. The advantaged are going to be able to survive and thrive in spite of the crisis, and the gaps will get greater for society.

There was a naive assumption when this first happened in the late winter that everything would be fine by September. Suddenly, it dawned on people by late June that it's not going to be fine.

HM: Some people in the public-health community say that reopening schools should be our top priority—over reopening restaurants, for example. But because we haven't done what we've needed to do as a nation to contain the virus, reopening schools isn't possible.

PR: Schools are more than just educational institutions. They perform an important childcare function. And that allows parents to go to work. So the implications of opening schools go beyond simply the implications for children in terms of their education and socialization. It goes to: what are the limitations on parents? And can parents come back into the workforce?

And so it's interesting that there hasn't been the sense of urgency about the issues associated with bringing people back to school until just the past few weeks. There was a naive assumption when this first happened in the late winter that everything would be fine by September. Suddenly, it dawned on people by late June that it's not going to be fine, and this hasn't gone away, we're not going to have a salve on the virus. In consequence, the same issues that were on the table in May and June are going to be on the table in August and September, and we haven't really figured them out. It takes some form of a high-level, energetic response. What you see in other countries around the world where their education systems are more centralized and more nationally oriented and top-down in nature is they have a much easier time settling on strategy and mandating practices and policies. That's totally in contrast to our highly local approach to governance of education. We have 13,000-plus school districts making decisions arrayed across 50 states and a few additional jurisdictions. We have no kind of unified, strategic response, which has proved to be a weakness in responding to the virus overall. And it's proved to be a weakness in dealing with education, because we're scattered all over the place and there’s not a clear set of strategies.

HM: What about the effectiveness or appropriateness of online learning for school-aged children?

PR: I think that it has its limitations and challenges. At the same time, it has its silver linings . We have a lot of negative associations with too much screen time for young people. But those negative associations tend to be related to what young people used to do when they were spending screen time recreationally. This is not the same as watching a movie or a TV series or playing video games. This has more to do with the quality of the educational programs. I'm not so worried about people being online if the content in the interaction is of a high quality, which good online education is.

What worries me is…the most primitive forms of online education involve just filming a teacher giving a lecture and students sit there passively and have no opportunity to respond or to think analytically or to engage in any way. So it's a waste of time. One of the things that we saw in a number of school districts in the immediate aftermath of school closing was an emergency response. They'd say, okay, we're going to go online tomorrow. We've not used these tools before, we have no idea what to do, but I'm going to post an assignment on a whiteboard on Monday, and I expect you to file a paper online with me by Friday. And that's our version of online education….That, obviously, is just a waste of time.

It's kind of Darwinian: every teacher on their own.

We at Harvard can see the contrast. Faculty here are getting a tremendous amount of help and support in terms of transforming our teaching from an in-person model to an online model. That takes a rethinking of the whole curriculum, familiarity with a whole bunch of tools, professional development, teaching fellows who are more adept at these technologies than a lot of faculty members. All these things come together and make it possible for us to make a transformation because we happen to be fortunate enough to work in an institution that has the resources to do it properly. But a lot of our school systems don't have those resources. So it's kind of Darwinian: every teacher on their own. And the teachers have, in many cases, very limited familiarity. This was not a medium they worked in before. Suddenly they're expected to do high-quality things here, and we haven't put in place the tools and resources to do it.

The positive part is there are a lot of good examples around. A lot of schools do this. A lot of countries are now doing it well. There are a lot of best practices to look at.But people in school systems are so overwhelmed right now—not just with how to do online education, but just how to balance their budgets, how to keep their staff safe, how to arrange transportation in the fall….If you're in a school system like Boston, you have a very complex, expensive transportation system. How are you going to bring that up to speed within health guidelines, which basically double your transportation costs.

So education leaders have so many other things on their minds that bearing down on the online piece, vetting all the products that are out there—curriculums and applications—let alone the problem in many of our areas of getting internet connections for students and families [is almost impossible].

And what do families do? What do you do if you have three elementary-school-aged children, and one or two working parents who are in essential jobs, who may not speak English themselves but have to be out of the house full-time? They have this equipment in the house that they've not used before….It just is a huge contrast with somebody living out in Wellesley [an affluent Boston suburb] with two professional parents….The Wellesley school system is doing a pretty good job of going online, and the parents are there to help them. Meanwhile, they've hired a teacher on the outside to work with their kids after school and weekends to keep them up. The contrasts are huge. They're bigger than they used to be when we had kids in school. So from an equity standpoint, that's what we worry about at the Education Redesign Lab.

Now it's every family for themselves—without the intervening institution of education to do any modest balancing. It was never a strong enough intervention to create equity, but at least it did something.

There are two things that we’ve been working hard on. One is [the] notion of having “children's cabinets”: either a formally authorized or an informal group convened by a mayor in a community, which brings to the table all the parties who care about children's wellbeing— people within city government, everybody from the school department, the health department, justice department, people in youth-serving agencies, community-based organizations, family organizations, unions, philanthropists, business people: anybody who cares about youth. Getting them around a table and thinking together about how are we going to meet the highly variable needs that children have in a crisis like this?

We've been counting on schools to provide health services, mental-health services, food services, in addition to education—and now none of that's happening and everybody's working in their own silo….We really need to design a cradle-to-career, longitudinal pipeline. The pipeline at the center is our formal K-12 system, higher ed, [and] early-childhood education. But wrapped around that is a system of opportunities and supports that come from the kind of social and financial capital you have in life. Eighty percent of children's waking hours are spent outside of school. So now we really have to come to grips with this. We have a moment of reckoning with the inequities in our society that have been revealed: here's how people really live. Here are the huge differences that exist between us within a society with such widely distributed income and wealth and advantage. And now it's every family for themselves—without the intervening institution of education to do any modest balancing. It was never a strong enough intervention to create equity, but at least it did something.

We're proposing children's cabinets, with which we've worked in a variety of communities across the country, putting together these kinds of organizations. The second thing that we're thinking hard about is that our existing education system is based on teaching to the average. It's a factory model built in the early twentieth century, for the batch- processing of students…it's one size fits all. It's based on the assumption that if we, at best, do for everybody equally, that will be an equitable education system.

The problem is equality and equity aren't the same thing. And fairness would dictate you meet children where they are and give them what they need, inside and outside of school, in order to help them be successful in life….We need systems for those who don't happen to be fortunate enough through the accident of birth to inherit social and financial capital, resilience and support and opportunity in their lives—we need to have those kinds of things in place for everybody….

So we're saying education ought to be more like medicine or business and customized to the individual. We need to see every child for her unique characteristics. What are her strengths? What are her assets? What are her needs? What are her challenges? What do we need to put in place in order for her to be successful? And it isn't just a school intervention. School on average is too weak an intervention to achieve equity in this society….We still have an iron-law correlation in our society between socioeconomic status and educational attainment. We've got to go beyond school to a more holistic, 360-degree, 365-day kind of approach to the lives of children.

We have way too many kids who go through our secondary schools virtually anonymously—nobody knows them.

What we're saying is that every child needs a success plan. It's like a running medical record that starts in early childhood and follows them all the way through their educational career to the point where they get a job. It keeps track of where they are, what's happening, what they need, what the interventions have yielded, and what the next chapter in their growth and development is. And in that way, we deal with some of these huge, yawning gaps that were big to begin with, but now they've gotten even bigger….We've had an enormous learning loss. And instead of saying, “Okay, we better do this year over,” we're saying, “Let's push these folks on [to the next grade] because we can't take on an additional cohort in our school.” So everybody gets pushed on, but now the gaps with which kids are approaching every grade level are wider than they were before. Some kids are going to need much more by way of tailored intervention to help them catch up with the other kids who've had a pretty good experience going through this….We have way too many kids who go through our secondary schools virtually anonymously—nobody knows them. Teachers are seeing 150 or180 kids a week. Their guidance [counselor] ratios are one to 400….One of the biggest losses in this whole COVID crisis is relationships. Students have had their relationship with their peers fractured, and had relationships with teachers and other folks in school who they were connected with fractured. We've got to bend over backwards to build relationships now. This notion of having a personal navigator—somebody within the school system who knows them, understands and knows and connects with the family, helps develop a portfolio of interventions that are necessary for that child and monitors that child throughout their educational experience—developing the success plan for each child, I think, is a way to respond individually to the needs of children.

HM: How would the student-navigator relationship work on a day-to-day level? How would they work together?

PR: In high schools, there’s a fair amount of practice already with advisories: instead of having a homeroom period each morning for 15 minutes, you'd actually have a 45-minute period, and a group of 20 students and a teacher, and that would start in freshman year, let's say, in a four -year high school. If I was your teacher, in that group of people, I have responsibility for all 20 of you. I have to get to know each of you individually. I have to meet with you and meet with your family and figure out what you need and how we're going to begin to develop a success plan for you. We have group discussions. That whole period is about the trajectory of that group through school, and I follow you for all four years. I'm with you. I'm your adviser, I'm your advocate. So it's ways of breaking down that anonymity. It's deepening the commitment of teachers to get to know their kids.

As a result of closing schools, families are at the center of education. For a long time, educators have given lip service to family involvement…for a lot of schools, it was just an afterthought, and they didn't really get around to taking it seriously…..And now there needs to be a really vital connection with parents. A lot of communication and collaboration— having elementary-school teachers connect with that family and open up regular channels of communication to meet periodically, to have a case-management approach to each child. That’s what it would look like. It means changing and deepening teachers’ responsibility. So it may be a fraction less formal teaching, and a fraction more personal engagement with students.

In our experience pushing this kind of work around the country, teachers love this. A lot of teachers say to us, connecting with students and making a difference in their lives is really why I went into teaching in the first place….So I think it’s a very positive thing for students, for families, and ultimately for the teachers. But it’s a transformative approach to take, and you’d have to develop systems to do this.

HM: What about the fiscal crisis hitting states and cities right now? How will that impact schools and their ability to make these changes?

PR: This is an enormous problem. It’s just on the horizon as the school year opens, because states are experiencing major losses in revenues, and localities to a lesser degree are experiencing losses in revenues. They’re having to cut back their budgets….So far, the federal government hasn’t seen fit to fund states and localities, although we think there’s probably some relief coming in this new bill [being written in Washington]. We’ll see what happens.

But even in the most optimistic projections, what’s happening is adding a substantial cost to cope with the elements of the pandemic that require greater expense for transportation, testing, all the spacing and cleaning and the professional development and the new technology tools, getting everybody hooked up to Internet— all kinds of expenses. Let alone extending what society seems to expect schools to do: stay on top of the food crisis, the health crisis, mental- health issues, student protection, student safety, and things of this nature.

Schools are being asked to do more than ever before. They were already being asked to do way too much relative to what they have the capacity to do. Now they’re being asked to do even more at a time when they’re being asked to cut back. Resolving that dilemma is a real challenge….Here in Massachusetts, transportation guidelines issued the other night call for a significant increase in bus monitors, for students to sit one at a time on a bench that used to be reserved for three. How are you going to bring everybody back to school? You’re going to need three times as many buses, and it’s just not affordable. These kinds of decisions are what superintendents, mayors, governors, and commissioners of education are grappling with, and there’s no easy solution.

There’ve been these moments in the history of education which turn us. This is one of those moments.

HM: Anything else you want to highlight about what the Ed Redesign Lab has been working on to support educators during COVID?

PR: I recently did a paper for the Centers for Disease Control in which I talked about a number of these transformative changes—everything from family engagement to strengthening relationships to the equitable distribution of technology—to take a lifelong -earning conception of this work to considerably strengthen what we're doing in early-childhood education.

I do think we’re at a transformative moment, and this emergency, while it is punishing and problematic in terms of equity in the short term, in the long term, it’s getting us to become familiar with tools and opportunities for growing and developing a more equitable system of child development and education in this country. If we make the most of the crisis by way of what we can learn, not just from our own practice, but around the world, and how we can do a better job of personalizing, customizing education to meet the needs of our students and families and use the tools and technology…then we have a chance of making this a turning point.

When Sputnik went up, it was a transformative moment in U.S. education because the country became deeply worried that we had fallen behind the Soviet Union, and we had to make a major effort to catch up. And that resulted in a lot of changes in the way we do think about financing education. Another one: we had the Nation at Risk report in the early ’80s and got a lot of publicity. It said if a foreign nation had done to us what we’ve done to ourselves in education, we would consider it an act of war. There’ve been these moments in the history of education which turn us. This is one of those moments. And the longer it persists, the more deeply we’re getting involved in new ways of working that engage our families, that have kids doing projects that use the tools or technology, that cause communities to think more broadly and convene children’s cabinets and cause educators to think about success planning and what we need to do to meet children where they are and give them what they need, inside and outside of school to be successful.

I’m an optimist. I’m hopeful that out of this, a lot of positive things are going to happen. But in the short run, if we’re not careful, the exact opposite can happen. This could exaggerate inequities that already exist in society, deepen digital divides, make opportunity gaps more profound than they already are. So we’ve really got to be attentive to issues of equity as we respond to this crisis.