“It’s a strange moment to have written a book where part of the argument is that things are changing less than you think,” said Ross Douthat ’02 on a sunny weekday afternoon in July. He was sitting on the back deck of his home in New Haven, Connecticut, overlooking a profusion of ocean-blue hydrangeas and the patchwork of his neighborhood’s backyards: swing sets, flower beds, trees, fences.

Like much of the country, the New York Times columnist had been holed up for months with his family, ever since the pandemic cut short the tour for his most recent book, The Decadent Society: How We Became the Victims of Our Own Success. Extending a line of thought that has incubated in Douthat’s columns for years, it brings together several strands of his world-view as a devoutly Catholic social conservative, reformist Republican, and assiduous analyst of American life.

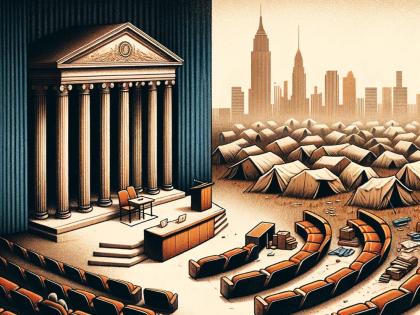

His argument is, basically, that the world’s richest nations have hit a dead end since the 1970s. Unmoored from a sense of a collective ambition and civilizational purpose (the book opens with a rapturous portrait of the 1969 moon landing), Americans and their counterparts in Western Europe, Japan, and the Pacific Rim have become trapped in political, cultural, and economic exhaustion. They’re having fewer babies: the U.S. birth rate is at its lowest point since 1920, when record-keeping began. (This baffles even social scientists, who take into account the past century’s migration from farms to cities and women’s move into the professional workforce.) They’re creating fewer technological breakthroughs (fancy phones, Douthat allows, but no flying cars, no colonies on Mars, no cure for cancer, no energy revolution). Popular culture is glutted with endless television reboots and superhero movies. And a polarized citizenry keeps fighting the same tired culture wars, as economic growth slows and political systems grind on in gridlock and institutional failure.

“We are aging, comfortable and stuck,” Douthat writes, “cut off from the past and no longer optimistic about the future, spurning both memory and ambition while we await some saving innovation or revelation, burrowing into cocoons from which no chrysalis is likely to emerge, growing old unhappily together in the glowing light of tiny screens.” All this, he writes, borrowing a term from the late cultural critic Jacques Barzun, is decadence.

It’s a grim picture. And, paradoxically, he argues, it could go on for quite a while: decadence does not necessarily mean imminent collapse. Even as it magnifies discontent, it is hard to break. Wealthy, aging societies tend to be cautious, not transformative; and outlets like drugs, pornography, and the internet siphon away fractious energy into escapism and fantasy. “You can go on Twitter or Facebook,” Douthat told an audience at the Brattle Theater in late winter, during what turned out to be one of the last stops on his book tour, “and reenact the 1930s or the 1960s in a kind of safe space where your arguments don’t have the real-world consequences that ideological clashes had in the past.”

The Decadent Society came out in February. In March, COVID-19 hit the Western world with full force, as millions got sick—including Douthat and his family—and millions of others stayed away from work and school and each other. By the summer, it was becoming clear the U.S. death toll would reach the hundreds of thousands. And on the heels of that rolling convulsion came another: the killing of George Floyd, a resurgent Black Lives Matter movement, the largest street protests in decades, and eruptions of violence in American cities. Increasingly, 2020 seemed determined to test Douthat’s thesis.

“To some extent,” he said in July, “I think the pandemic has revealed more about the potential fragility of the world that I’m describing.…I think it shows that when you get this kind of shock, if it’s big enough, some of the patterns I was depicting as being pretty resilient can be disrupted pretty quickly.” The book’s penultimate chapter offers a series of imagined scenarios in which decadence collapses into catastrophe: worldwide economic meltdown, climate change, sudden mass migration. “When I was writing them, they felt very speculative,” he says. “But actually, I probably should have speculated more.” At the same time, COVID-19 has laid bare the starkness of American decadence—in the Trump administration’s mismanagement and incapability, in the deepening stalemate in Congress over continuing legislation to fight the crisis, in the emergence of mask-wearing as another front in the culture war.

And yet, he says, it’s also not hard to see how the pandemic might only push the United States even deeper into decadence. That was the gist of a late June column suggesting that at the end of the strange hiatus imposed by the coronavirus, Americans might reemerge to find even more consolidated power and ideological conformity, with human-scale institutions like neighborhood restaurants, local newspapers, and small churches weakened further. “There’s clearly going to be a further dip in birth rates, and more consolidation in a lot of industries,” he says. “Big companies are going to weather this better than small companies. Small schools will go out of business, while Harvard does fine. We may wake up in 10 years and find that the system has absorbed the shock and the result is even further decadence.”

The implications of Black Lives Matter are harder to see as yet, Douthat says. “We are having mass protest politics to an extent that we haven’t really had in decades, and much more sustained and culturally significant than the Iraq War protests and Occupy Wall Street.” Through the summer, the movement generated real energy around the issues of systemic racism and inequality, which in turn led to real turnover in elite institutions. (He notes as an example The New York Times itself, where in early June an op-ed by Arkansas senator Tom Cotton ’99, J.D. ’02, advocating military force against protesters sparked intense backlash and an internal revolt that forced the departure of the opinion page’s lead editor, James Bennet. In a disquieted column after the fact, Douthat examined “how liberalism, and the liberal media, are changing before our eyes.”)

What remains to be seen about Black Lives Matter, he says, is how much the protest movement can change the deeper societal situation: whether major police reforms really do take place, whether reparations for slavery are finally pushed through, whether a larger pattern of racial justice reform takes shape and moves forward. (After Floyd’s death, Douthat advocated rolling back police union protections and providing more funding—not less—to hire better-caliber officers, including minority candidates.) “The cynic in me sort of expects that in the end, the rhetoric will be the reality,” he says of the protests’ impact, “and that there will be a new, more left-wing vocabulary in elite spaces and a rebalancing of power among affluent professionals, but not outside of that.” In other words, decadence abides—for now.

When Douthat’s colleagues and other pundits—both critics and admirers—talk about his conservatism, they often use words like “eclectic” and “unexpected” and “eccentric.” Reliably right-wing on social issues like abortion and gay marriage, he is harder to predict—and sometimes more complicated to parse—on others: economic policy, education reform, health care, foreign policy. In 2017, he proposed reparations for slavery, but as a one-time payment to descendants of slaves, in exchange for an end to race-based preferences in hiring and admissions: “It would hardly eliminate racial disadvantage, but then again neither has 50 years of affirmative action,” he contended. “What it would offer is a meaningful response to an extraordinary injustice, but a response that does not involve permanent discrimination.” In a heavily caveated column on the Green New Deal, he found room to praise its direct-spending approach to infrastructure and its “sweeping ambition,” which, in its own way, counters decadence by “trying to offer not just a technical blueprint but a comprehensive vision of the good society.”

Last November, as the presidential primary heated up, Douthat put forward a “conservative’s case” for Bernie Sanders as the Democratic nominee, based on the Vermont socialist’s “anti-plutocratic goals”—which Douthat shares—and a seeming reluctance toward, as Douthat put it, “progressivism’s zeal for culture war.” Sanders, he supposed, would be the liberal most likely to tax the rich and leave cultural conservatives alone. “What’s interesting with Ross,” says Michelle Goldberg, a New York Times liberal columnist and a co-host with Douthat on the newspaper’s podcast The Argument, “is that there’s some overlap for him with the emerging socialist left. There are weird places where his world-view is maybe not that different from [Catholic socialist and regular Times columnist] Liz Bruenig’s.”

National Review writer Michael Brendan Dougherty, a fellow conservative and close friend of Douthat’s, offers a related assessment. “I’m not sure if it comes across in his writing,” Dougherty says, “but I don’t think either of us feels particularly at home in the Republican party, as such—like, the business class and evangelical personality of the GOP.…I think a lot of people think his project is about elective politics—and certainly he touches on it—but what he’s doing is about something different and beyond that. It’s not partisan.”

Even on religion, Douthat’s most straightforwardly uncompromising subject, his thinking tends to take unexpected, provocative turns. Conservative commentators routinely decry Americans’ drift toward secularism, but Douthat wonders where all that devotional energy might have landed. And goes searching for it. In his 2012 book, Bad Religion, he described American Christianity as fragmented and decaying—but not into simple unbelief. On the cultural left, he argued, Christianity had devolved into vague spirituality, self-help, and the “church of Oprah”; on the cultural right, into jingoistic, politicized evangelicalism and the prosperity gospel of preachers like Joel Osteen, whose ministries all but ignore sin. More recently, Douthat detected a “palpable spiritual dimension” in the social-justice activism after the George Floyd killing. A July column explored the struggle for power within the liberal order, waged against the old guard’s wealthy elite by educated, progressive, but not necessarily rich “post-Protestants,” whose “mainline” moral sensibility has survived, he argued, even as their metaphysical belief ebbed away.

Sometimes, Douthat’s heterodoxy and experimentation, his impulse to question the well-worn grooves of elite consensus, lead him down avenues that critics find problematic. In 2017, he contemplated an affirmative case for French politician Marine Le Pen, leader of the far-right National Rally party. In 2018, after a self-identified “incel” (involuntary celibate) drove onto a crowded Toronto sidewalk, killing 10 people, Douthat mused on the concept of sex robots and “the redistribution of sex.” Readers bristled; some mistakenly believed he was endorsing a right to sex—he wasn’t—but even critics who read his column with more nuance complained that it overlooked the virulent misogyny fueling the incel movement. That same year, New Yorker staff writer Vinson Cunningham noted a tendency in Douthat for “breezing past the most radical implications of his ideas.” Cunningham was referring to a column in which Douthat offered a rationale for why liberals should welcome White House policy adviser Stephen Millert into immigration-policy talks, “presenting several benign-sounding arguments for Miller’s pretty gross position on the subject,” Cunningham continued, “without ever letting slip whether he shares it.”

Now on the cusp of 41, Douthat has at last caught up with the older man’s bearing he’s had since his twenties (“a promising young fogy,” Slate once needled). Sitting on his deck, or walking in the forested park near his home, he comes across as thoughtful and warm and funny; there’s a gentle, easy way about how he speaks, and how he listens. That demeanor, and his curious, heterodox view of the world, arose from an unusual childhood. He grew up in New Haven, about a 10-minute drive from the house he now shares with his own family: his wife, Abigail Tucker ’02, also a journalist and author (whose book Mom Genes: Inside the New Science of Our Ancient Maternal Instinct comes out this spring), and their children—three girls and a boy, the eldest nine and the youngest born in April amid the chaos and swirl of the early pandemic.

When Douthat was a child, his family’s home life was profoundly shaped by his mother’s chemical allergies. Perfume, pesticides, and dyes caused painful, debilitating reactions. Douthat met friends at the park instead of bringing them home, where the detergent on their clothes could trigger a reaction. The search for food she could safely eat became a perpetual family project. “We basically ate health food before it was cool,” he says. “Whole Foods didn’t exist then, so we would go to, like, the vegetarian restaurant run by ex-hippies.” For a while, they tried a macrobiotic diet; the whole family attended a two-week camp one summer, centered on macrobiotic food. “So, we lived in these unusual worlds.”

To find relief, Douthat’s mother also turned to the world of faith. Raised Episcopalian, she attended a sermon one night given by a Pentecostal faith healer named Grace James and had a transformative mystical experience. For three years thereafter, the family followed James around New England, to Elks Lodges and tiny church basements and dilapidated music halls and high-school cafeterias. Later, the family embarked on what Douthat has called a “tour of American Christianity,” attending evangelical and charismatic services in church after church—for a time, his parents helped run a small charismatic congregation at Yale—before converting to Catholicism in the mid 1990s, when he was 17. Temperamentally, the Catholic Church suited him. “I had never reacted well to the culture where, you know, someone’s putting their hand on your shoulder and saying, ‘Can you testify to how the Lord Jesus has changed your life?’ I wasn’t up for that. I was very much up for a church where you could go and sit in the back and memorize the prayers.”

His newly rooted religious life dovetailed with a growing social conservatism. He was reading authors like G.K. Chesterton, C.S. Lewis, and J.R.R. Tolkien. His parents, originally left-leaning, had been moving rightward, too, and they began subscribing to the conservative religious journal First Things, founded and edited by Richard John Neuhaus, a Lutheran minister who had converted to the Catholic priesthood. Neuhaus became an intellectual guide for Douthat. “That helped tug me into some kind of formal conservatism,” he says. There was also, he admits, “maybe a touch of mild rebellion against my social milieu. I went to pretty conventional, liberal, secular private schools around New Haven. And I’ve always been sort of contrarian and defined myself against my social surroundings a little bit.”

Douthat’s column gives liberal readers a primer of social conservatism.

At Harvard, Douthat swam a little harder against the current. He concentrated in history and literature, edited the conservative student newspaper The Harvard Salient, and wrote a sometimes-combative column for The Harvard Crimson. Three years after graduation, his memoir, Privilege: Harvard and the Education of the Ruling Class, offered an early, pungent critique of meritocracy, which he had come to see as an “ideological veneer” beneath which “social and economic stratification is the reality.” Today that idea is salient on both the left and right—but 15 years ago it was still a fairly esoteric view, a strand of Douthat’s evolving political eccentricity. Describing left-wing student activists in Privilege, he declared: “For all that I abhorred most of their ideas and nearly all their tactics,…[t]hey at least shared my sense that there was something wrong with Harvard, and with the entire culture of meritocracy and achievement and cheerful capitalism—something that had to do with greed and ambition and corruption, with the lavish spreads that awaited us at McKinsey and Bain recruiting sessions and the hollow-eyed weariness of the immigrant women who cleaned up the mess afterward, long after we had sought out the bars and then our beds.”

After Harvard came a seven-year stint as a researcher, editor, and blogger at The Atlantic interpreting politics, culture, religion, and the media (he also began contributing movie reviews to the National Review, a sideline that continues). And then in 2009, The New York Times hired him to succeed William Kristol as a conservative voice on the editorial page. At 29 years old, he was the youngest columnist the newspaper had ever hired.

During the decade-plus since then at the Times, Douthat has settled into an editorial task that he acknowledges is somewhat (maybe mostly) quixotic: to push for public morality that aligns with his religious convictions, and also to advocate for “serious conservative policymaking that accepts the existence of the welfare state and tries to turn it to conservative ends”—namely, support for working families with children. Those twin goals echo back, he says, to Dwight Eisenhower and the first-generation neoconservatism of the 1970s, which made a kind of peace with the New Deal while pushing against liberalism’s more radical impulses.

“So that’s the project I’ve tried to engage in,” he says. In 2008, Douthat and conservative journalist Reihan Salam ’01, now president of the Manhattan Institute, distilled this philosophy into their book Grand New Party, which diagnosed the Republican failure to serve the working class and advocated pro-family measures like expanded child tax credits, pension credits for household labor, tuition credits for years spent raising children, wage subsidies to help single men become more marriageable, and “progressive cost-sharing” on health care, so that the wealthy pay more out of pocket.

“Ross is interesting, because unlike a lot of conservatives, he doesn’t have this complete insurgent attitude toward the culture and to politics,” says his friend Dougherty. “One of his virtues is that he stays grounded to experience.” Notre Dame political scientist Patrick Deneen puts it another way. Douthat, he says, is “skeptical of the more traditionalist conservatism, which sees modern society as deeply corrupt and needing a kind of wholesale reset.” Deneen, who wrote Why Liberalism Failed (2018), leans more toward the wholesale-reset camp. “In a way,” he says, Douthat’s response is “an even more conservative instinct, right? Because he thinks, well, we have to kind of muddle along with what we have. He’s articulating a position of, what can we conserve of modernity?”

“Instead of leading a giant conservative battleship like The National Review, he’s a guy sidling up to you at a party that you aren’t sure why he was invited.”

At the Times, Douthat straddles a strange divide. Arguably more conservative than his right-leaning opinion colleagues, who tend more toward libertarianism, he acts as a kind of tour guide to social conservatism for an audience that is mostly hostile to its ideas. “Instead of leading a giant conservative battleship like The National Review, he’s a guy sidling up to you at a party that you’re not sure why he was invited,” Dougherty says. Yet Douthat is also a favorite interlocutor for many liberal thinkers and pundits—and, anecdotally, readers. “He is always talking to liberals, not haranguing them or lecturing them, but really talking to them, you know?” says Goldberg, his podcast partner. “So liberals feel like they can talk to him.”

“He’s a brilliant critic of many liberal mistakes,” adds Yale historian and legal scholar Samuel Moyn, J.D. ’01, who co-taught a Yale Law School course on conservatism with Douthat in 2018; the two will teach an undergraduate course on the “crisis of liberalism” next spring. “He’s softer on the conservative mistakes, but he wants to identify those, too.” A scholar of human rights’ Christian roots, Moyn overlaps with some of Douthat’s economic-policy objectives, but from a progressive viewpoint. “Ross is a very gifted pedagogue,” he says, “and willing to engage without acrimony with all comers, as you can tell from his columns and his Twitter feed.”

Goldberg, too, calls Douthat a “brilliant culture critic” and says he’s often “extremely penetrating” even when he’s wrong. “He always argues in good faith, and he recognizes the same reality that I do,” she says. “He just comes to a different conclusion, because he has a very different idea of what a good society looks like. I mean, his version looks to me like a theocratic hellscape, but he’s always honest about where he’s coming from and where reality complicates his ideological priors.”

For Douthat, the facility for dialogue across boundaries is partly circumstantial. “I’ve never been in a situation where I existed without talking to liberals,” he says. Much of his family is liberal, as are most of his college friends. Plus, “I’m here in New Haven,” a blue-voting city in a mostly blue-voting region. “I have a stake in the liberal parts of the country, the liberal institutions that nurtured me. I don’t have a heartland home to retreat to.” But Douthat’s appeal is also temperamental. He’s comfortable with complexity and uncertainty and disagreement. And he has cultivated, out of necessity, a certain ironic detachment from controversy: he keeps his cool, and he doesn’t get defensive. “As a kid, I had a principal who at one point said something like, ‘You know, Ross can dish it out, but he can’t take it.’ And I think I’ve really taken that to heart. A crucial aspect of actually growing up for me was learning how to be a sharp-tongued obnoxious kid and taking the flak that comes with that.”

The Trump era, though, has strained that dynamic. “I’ve had conversations where a liberal friend says, ‘Oh, my friend asked me, how can you be friends with Ross?’” he says. “That kind of thing floats up more than it ever has before.” Douthat has been at times a sharp critic of the president; his columns and The Decadent Society offer withering assessments of Trump’s incompetence, his narcissism, his venality and corruption and depravity. He did not vote for Trump in 2016—in fact, some of his most alarmed columns came in the run-up to the election—and has written that the president doesn’t deserve a second term. But at the same time, Douthat maintains some sympathy for the white working-class voters who supported the president out of a sense of economic desperation (they are the “Sam’s Club Republicans” he advocated for in Grand New Party), even as he also acknowledges the “darker forces” of racism and xenophobia that animate many voters’ attachment to Trump.

More disturbing to liberals, Douthat believes, is his skepticism about what he calls the “rhetoric of emergency” about Trump.

Perhaps more disturbing to liberals, Douthat believes, is his skepticism about what he calls “the rhetoric of emergency” about Trump’s presidency. He is sometimes reluctant to lay the country’s problems as fully at Trump’s feet as others do, and finds the president more farcical than threatening, his cruelty and malevolence hampered by incompetence. In the face of what looks to many like incipient autocracy, Douthat keeps a stubborn calm. Even after the pandemic hit, he reiterated that view: the crisis offered Trump the opportunity to consolidate power, he wrote in May, but “our president is interested in power only as a means of getting attention.”

A similar skepticism helped germinate The Decadent Society. As a teenager in the 1990s, he came of age and political awareness with Francis Fukuyama’s The End of History. The United States had won the Cold War, the internet was coming online, and democracy seemed to be spreading around the world: the endpoint, Fukuyama argued, of humanity’s ideological evolution. Says Douthat, “It was the last period of futuristic optimism.”

And then, in the fall of his senior year, 9/11 happened. “And at the moment when I entered journalism, everyone—but especially conservatives—were saying, ‘Now the end of history is over. History is returning. We’re back in some grand struggle for civilization, against a rival ideology.’” Except that’s not how it played out. “All it led to was, you know, the Iraq War, which was disastrous and turned out to be based on wild threat inflation of Saddam Hussein as a world-historical menace, when really he was just a tinpot dictator.” Then came the Great Recession of 2008, “and you had people on the left saying the end of history was over and, with Occupy Wall Street, there was going to be this radical transformation that also coincided with the election of Barack Obama, who was seen as this kind of messianic figure.” But Obama turned out to be more technocrat than messiah, and by 2012 he was running against Mitt Romney, “the embodiment of the Republican version of the status quo.”

And so, “there were these two straight moments in my adult life when we were told that everything was changing, and in fact, the status quo turned out to be quite resilient, and what Fukuyama was describing in 1990 still described the world. And that we were still in this sort of weird, post-historical period.” The moment when things really did change, he believes, was in the years leading up to 1970. The Baby Boomers’ youth was a period of genuine creativity and transformation—“an incredibly fertile, and interesting, and dynamic time,” he says, “but they won the victory over the past too completely. They so routed the forces of the older establishment and older institutions that they were sort of left alone without having fully built something new that could be passed down and reworked and transformed by subsequent generations.” Pre-Boomer churches, colleges, civic organizations: “These are the kinds of things that round people in ways that lead to human flourishing over the life cycle. I think if the post-1970s world was one standard deviation more culturally conservative, then you actually would have had more of a base for future growth, for future dynamism.”

One question seems to linger in the background of Douthat’s writing on decadence, unmistakably felt but never quite articulated: how to live? Amid the sterility and decline, in a society that has lost the power to grow, how should a person go forward through life?

The book hints at the possibility: “It is not always easy,” he writes, “but human beings can still live vigorously amid a general stagnation.…The decadent society, unlike the full dystopia, allows those signs of contradictions to exist, which means that, under decadence, it always remains possible to imagine and work toward renewal and renaissance.” Douthat’s broad prescription for how to live involves the “morally meaningful choices” of lived reality rather than the distraction of virtual escapes. “You’re looking,” he says, “for forms of existence that are more radical and extreme than just floating along.…Try to be a person who is seeking out encounters and experiences that are potentially transformative, or to be solving discrete problems, or involved in building communities that are capable of changing people’s lives.”

That’s Douthat’s hope for his current book-in-progress, about his experience with Lyme disease. In 2015, soon after he and his family had moved from Washington, D.C., to rural Connecticut, he was bitten by a tick: “We’d bought an antique farmhouse with fields and barns and everything,” he says. “And it turned into a nightmare.” The family relocated to New Haven, and Douthat spent years suffering—“wrecked and despairing,” he has written—with chronic Lyme, an illness about which, he says, “there’s immense controversy” in the medical literature over “whether it even exists and how to treat it.” The list of symptoms that patients often report, after the initial telltale fever and bulls-eye rash subside, is vast and bewildering: severe headaches and shooting nerve pains, facial palsy, swollen joints, heart palpitations, shortness of breath, inflammation in the brain and the spinal cord.

Douthat is much better now. He still has “weird” symptoms sometimes, he says, “but I’ve learned a lot.” The past few years have been an ordeal of misdiagnoses, multiple antibiotics, and a medical profession inclined, he believes, to give up on Lyme disease patients who don’t get better right away. In writing the book, he hopes to transform that hardship into meaning, with a firsthand exploration of a little-understood chronic disease, and of the knowledge that might be used to treat it. “My least decadent book,” he jokes.

Some of his writing about the pandemic offers a glimpse of the shape the book might take. In March, he wrote about the confusion and distress of conflicting coronavirus test results; in April, he wrote about pain and grief and the search for meaning in the pandemic’s suffering. And in a tender, poignant column this past August, he offered advice to the pandemic’s “long-haulers,” people for whom the virus has lasted months instead of weeks. He spoke from his own experience—of Lyme disease, but also of COVID-19, which kept him sick throughout most of the spring. It is not hard to see shades of his mother’s tribulation as well—and perhaps also his father’s: an attorney who turned to poetry after a midlife illness, and published a well-received book of movingly personal poems. In that August column, Douthat wrote, “Trust your own experience of your body.” And: “If your doctor struggles to help you, you’ll need to help yourself.” And: “Ask God to help you.…I mean this very seriously.” Finally, he offered this note of reassurance: “You can get better,” he wrote. “That belief is essential. Hold onto it.”